- September 25, 2025

Competence: The Currency of Confidence in Testing Laboratories

Origins, models, evidence and practical examples for laboratory leaders

Keeping staff competent is a core requirement of accreditation and a practical necessity for accurate testing. Accreditation standards (for example ISO/IEC 17025 and ISO 15189) explicitly require that laboratory personnel are competent — not merely trained — and that competence be defined, assessed and maintained.

Short history & why it matters

The modern competency movement began as a challenge to traditional reliance on IQ and aptitude tests. In 1973 David C. McClelland argued that organisations should “test for competence rather than for intelligence,” and developed methods (behavioural event interviewing, job competence analysis) to identify the behaviours that actually predict superior performance.

Later research and applied models (notably Competence at Work by Spencer & Spencer) turned these ideas into practical frameworks that HR and training teams use today. These frameworks demonstrated how competency models could be used across hiring, development and performance management.

For laboratories the consequence is direct: competence drives accurate results, reduced risk and audit readiness. Numerous accrediting bodies commonly cite gaps in competency assessment and documentation among the top nonconformities during assessments. Addressing competence isn’t optional – it’s a route to better quality and fewer findings.

”Without data you’re just another person with an opinion.”

W. Edwards Deming

Models that help us understand competence

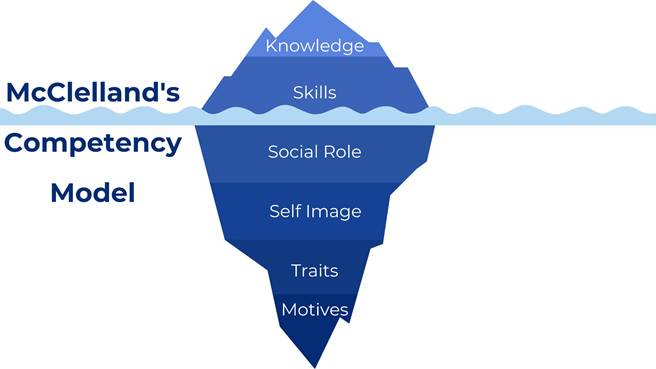

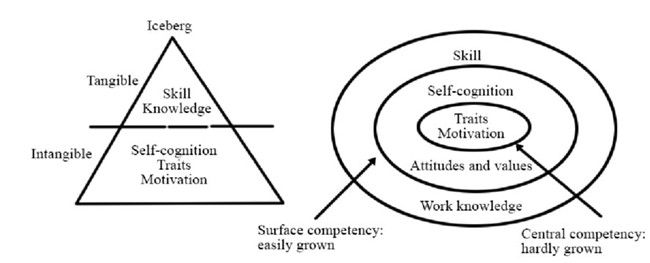

Iceberg model (McClelland / McBer)

The iceberg metaphor remains useful: knowledge and skills (what you can easily see and measure) are above the waterline; traits, motives, self-image and values (which drive consistent behaviour) are below the surface and harder to measure. Effective competency systems look at both visible and hidden elements because technical ability alone doesn’t guarantee performance.

Competency clusters (Spencer & Spencer)

Spencer & Spencer describe competencies as clusters of knowledge, skills, abilities, motives and traits that predict superior performance in specific roles. They emphasise job-analysis grounded in observation and evidence – which aligns well with laboratory practice (proficiency testing, direct observation, objective performance criteria).

What the standards require (practical implications)

ISO/IEC 17025 (personnel requirements) makes the laboratory responsible for defining competence requirements for each position, demonstrating personnel meet those requirements, and maintaining records (training, authorization, monitoring). That means: job descriptions, competence criteria, assessment evidence, and authorization records must be part of the management system.

Practical implication: don’t rely on attendance records alone. Accreditation assessors want evidence of application — recorded observations, proficiency testing results, supervisory sign-offs and corrective actions where performance drift is identified. CAP and other regulators require periodic re-assessment (for some tests semi-annual during a first year then annually) — reinforcing the need for a scheduled, documented program.

So, how do you do this?

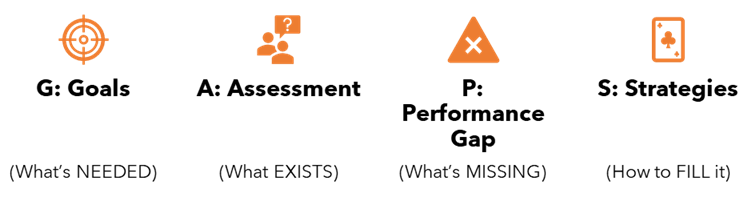

The GAPS approach

Use a GAPS approach as an operational model:

- Goals — define required outcomes and performance criteria (method accuracy, turnaround time, documentation completeness).

- Assessment — measure current performance (observation, PT results, knowledge tests).

- Performance Gap — identify concrete shortfalls.

- Strategies — targeted interventions (mentoring, SOP refreshers, revalidation of technique).

This creates a closed loop from organisational requirements to measurable development.

Select your assessment technique

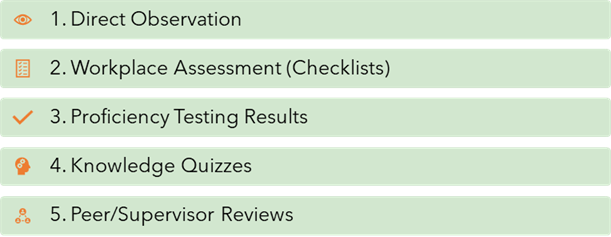

Assessment techniques — strengths & typical evidence

Use a mix of methods to ensure validity, reliability and sufficiency of evidence:

- Direct observation / workplace assessment: checklists with objective performance criteria (e.g., correct pipetting technique, correct calibration record completion). High face validity and ideal for procedural tasks.

- Proficiency testing / external quality assessment: objective evidence of performance relative to peers; valuable for demonstrating ongoing competence for methods.

- Knowledge checks and short quizzes: confirm understanding of procedure rationale and critical limits.

- Simulator or blind challenges (where safe): mimic real-world errors and observe responses.

- Peer and supervisor review: supplements objective checks with contextual insight (attitude, communication).

- Customer feedback and trend data: error trends, customer complaints or rework rates can signal competence drift.

Evidence must be valid, authentic, current and sufficient — documented and linked to the job’s competence criteria.

Developing competence

Practical examples and interventions

Example 1 — New method authorisation

- Goal: technician performs method X reliably.

- Assessment: supervised runs with pass/fail criteria, blind QC sample, successful PT result.

- Strategy: targeted coaching, competency checklist signed by authorising supervisor, re-assessment at defined intervals.

Example 2 — Reducing retraining costs while maintaining quality

- Problem: repetitive generic classroom training with limited impact.

- Solution: adopt risk-based, just-in-time learning — short videos and job aids for low-risk refreshers; intensive hands-on assessment for high-risk methods. Use trend data (error rates, PT failures) to trigger retraining rather than fixed schedules alone. This approach aligns with Deming’s emphasis on data-driven action. Wikiquote

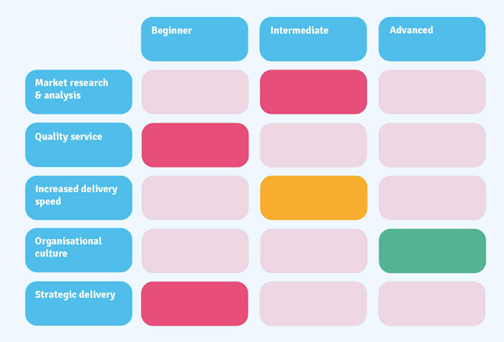

Example 3 — Competency matrix for career stages

- Map each role and seniority level to competencies (beginner → intermediate → advanced).

- Provide evidence types (observation, PT, logbook) and authorisation thresholds for each cell. This supports mobility, succession planning and defensible assessor decisions.

- Use role-specific matrices with Red/Amber/Green ratings for each competency

Current opinion and recent emphasis in the field

Recent guidance from accreditation and professional organisations emphasises:

- Traceability and recordability — every declared competency event should be traceable (who assessed, when, against which criteria).

- Integration with risk and quality systems — link competency outcomes to audit findings, nonconformities and corrective actions so development is clearly risk-driven.

- Digital capture and dashboards — many labs are adopting simple competency management modules to reduce administrative load and produce dashboards showing currency and gaps. This improves transparency to management and assessors.

Academic and HR research supports that competency models are most effective when grounded in job-specific behavioural evidence (behavioural event interviews, observed critical incidents) and when tied to business outcomes — the original promise set out by McClelland and developed by Spencer & Spencer.

Practical checklist for laboratory leaders

- Define role-specific competence criteria — include technical steps, decision points and required outcomes.

- Design mapped evidence — for each competency, list acceptable evidence (observation checklist, PT, knowledge test).

- Schedule assessments by risk — high-risk activities more frequent; use data triggers for retraining.

- Record and authorise — keep assessor sign-offs, dates, remediation steps and re-authorisation documented.

- Use simple dashboards — give managers a quick view of currency and gaps so resources are targeted.

Closing — an evidence-based culture of competence

Competence is not a paper exercise; it is an organisation’s documented ability to deliver reliable results, repeatedly. The competency movement began as a demand for better predictive validity in workforce decisions and matured into practical tools for talent and quality management. For laboratories, this means building systems that link clear competence criteria, robust assessment, and targeted development — all evidenced in the management system. As McClelland asked us to do: focus on the behaviours that predict success; and, as Deming reminded us: use the data to make those decisions defensible.

“Competence is the currency of confidence in testing laboratories.”

Key references & further reading

- McClelland, D. C., Testing for Competence Rather Than for “Intelligence” (1973). Gwern

- Spencer, L. M., & Spencer, S. M., Competence at Work: Models for Superior Performance (1993). Google Books+1

- A2LA: Explaining ISO/IEC 17025 competency requirements. A2LA

- CAP: Common deficiencies & competency assessment guidance. WhiteHat Com

- Industry commentary on lab deficiencies and competency frequency (MedLabMag, ASCLS). MedicalLab Management Magazine+1